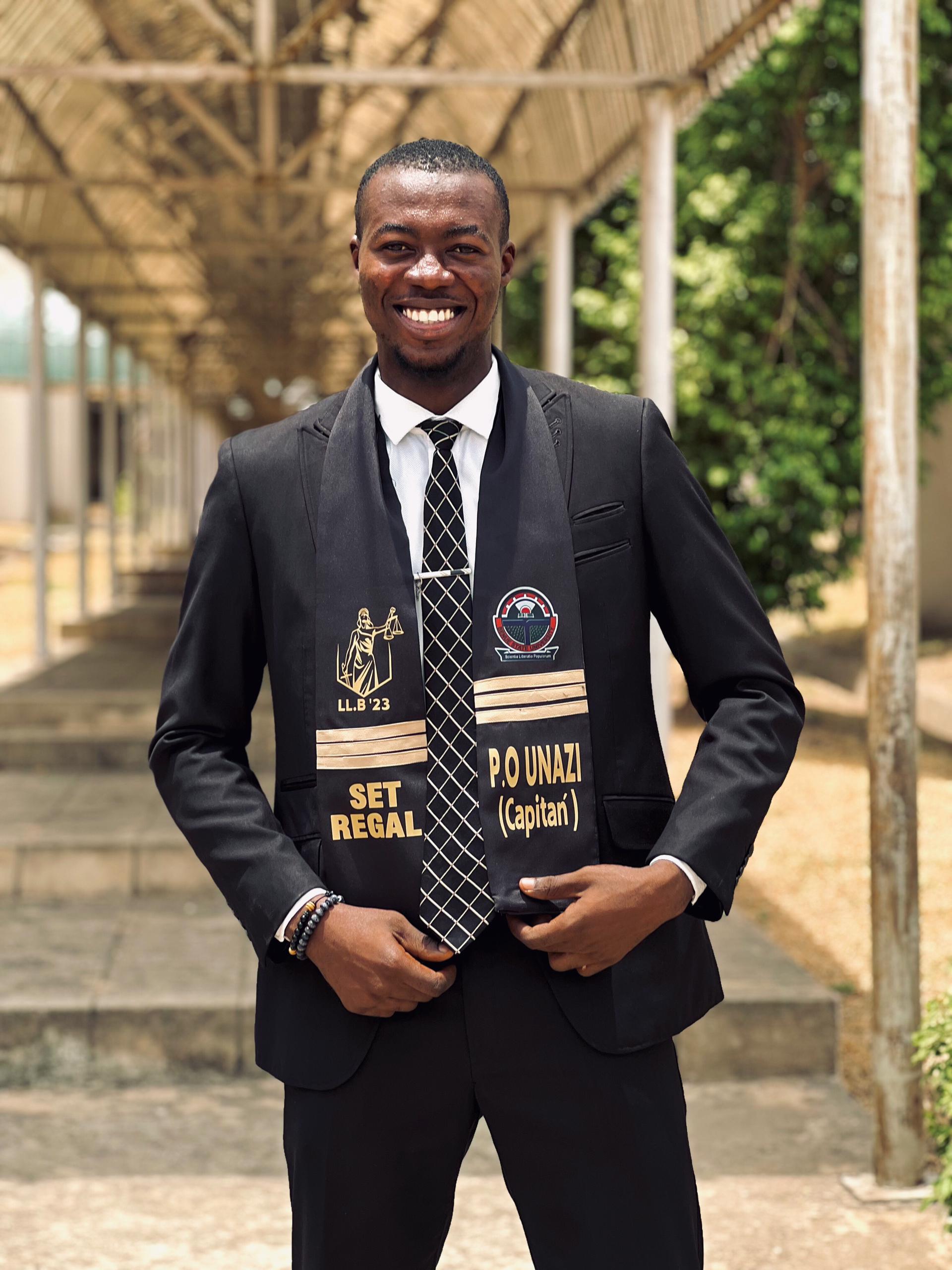

Sometime in the earliest part of January 2023, we appeared before a Magistrate Court in Nigeria in a criminal matter for a client who was being arraigned in court for what started out as a breach of contract. Before the matter which we were in court for was heard, another criminal matter was heard and a motion to remand the accused person was moved and granted by the court. The brief fact of the matter was that, the complainant entered into a contractual agreement with a company to supply some goods. The company was outside the State of residence of the complainant and he got to know about the company through his friends who had directed to him to someone who was currently dealing with the company and getting goods from them.

The accused person proceeded to give all the necessary information about dealing with the company to the complainant and his friends. After they conducted their due diligence the complainant and his friends decided to enter into a contract with the company and some millions of naira was transferred to the company’s account as consideration for the supply of goods. All the negotiations and transactions between the complainant and the company was done remotely. Some months after the money was paid to the company, the goods were still not supplied; only for them to reach out to one of the company’s directors and they were informed that the company was going through some challenges that stalled the supply of the goods. The director reassured the complainant and his friends that immediately the issues were sorted out, the goods would be supplied. Unfortunately, the goods were not supplied neither was the money refunded. Disappointed with the outcome of the transaction, the complainant wrote a petition to the police and the accused person who gave the information about the company was arrested.

The basis of the accused person’s arrest was that he was an agent of the company. According to the prosecutor the accused person had put himself in a representative capacity as an agent of the company and in fact, was guilty of defrauding the complainant. After the accused person was arraigned before the magistrate, the prosecutor moved a motion to remand the accused person in prison for fraud. The magistrate granted the motion and ordered that the accused person be remanded in prison.

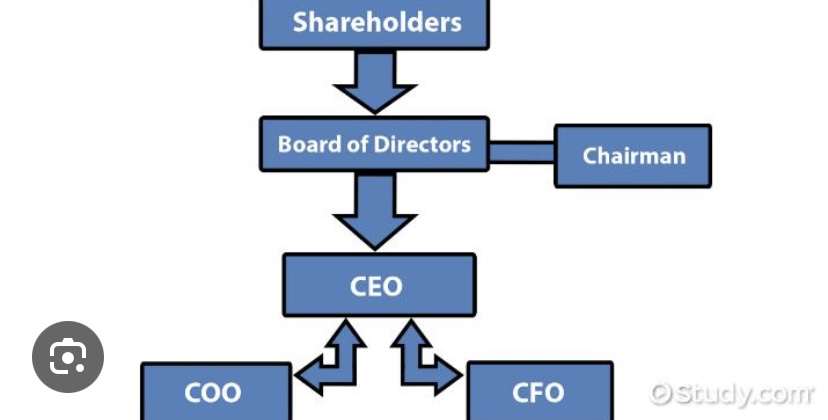

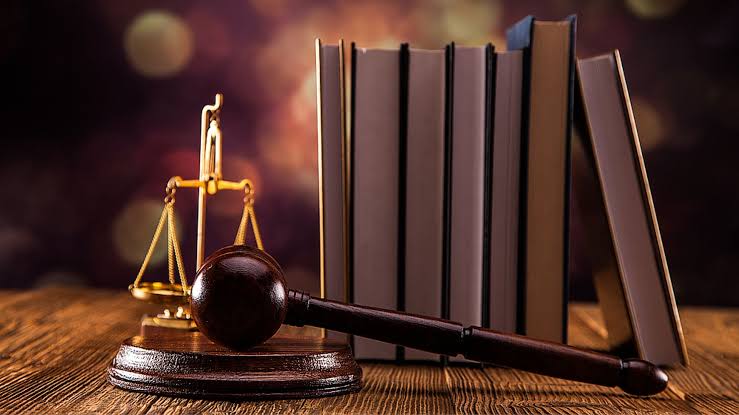

This discourse is not to highlight the constitutionality or raison d’etre of remand orders in Nigeria, as that should be a topic on its own. What we are concerned about here is the issue of corporate liability and the principle of separate legal personality as it relates to corporate bodies. Corporate liability entails the extent to which a company; as an artificial person with legal capacity can be held liable for the acts and omissions of the natural persons under its employment. Just like humans, a corporate body has legal capacity to sue and be sued, in this regards it can be held civilly and criminally liable. However, since a corporate body is an artificial person with legal capacity, it only acts through the officers and agents of the company. In this regards, when an agent, officer or employee of a company carries out any action or inaction in relation or on behalf of the company, if such actions and inactions come with any legal consequences, the company will be held liable and not the natural person.

Flowing from the above, it should be pointed out that position of the law on corporate liability of a company also hinges on the principle of vicarious liability and these principles have been enacted as provisions in the company regulations and laws of most, if not all legal systems. Taking cognizance of Nigeria’s Companies and Allied Matters Act 2020, Section 89 provides that; “any act of the members in general meeting, the board of directors, or a managing director while carrying on in the usual way of the business of the company, shall be treated as the act of the company itself and the company is criminally and civilly liable to the same extent as if it were a natural person”.

It should be clearly understood that a company is not only particularly liable for the actions of the officers of the company or its employees but also anyone authorized to act in a representative capacity as an agent of the company. In differentiating officers of a company from agents of a company, it should be clearly pointed out that while all officers of the company are agents of the company, not all agents of the company are officers of the company. As earlier pointed out, the company as an artificial person can only act through its officers, agents or employees who are natural persons. However, a common and trite principle regulating companies in different legal systems and with particular reference to Section 90 of the aforesaid Companies and Allied Matters Act applicable in Nigeria, a company can only be held responsible and liable for the actions and inactions of the officers, agents or employees if it had earlier authorized such an person to act on its behalf either impliedly or expressly. Authority to act on behalf of a company may be given prior to the action or ratified after the action has been taken.

For corporate criminal liability, it has been judicially held as a general rule in Nigeria that there is no vicarious liability in actions that are criminal in nature. Put more succinctly, a master cannot be held responsible for the criminal action of his servant except of course the criminal act was committed in the course of employment. Therefore, the law is clear that if an officer, agent or employee of a company commits a criminal offence, except such an offence was done in the course of employment, the company cannot be held liable for it.

On the other hand, is it possible for the officers, employees or agents of a company to be held liable for actions or inactions of a company? Since we already know that the company acts through the natural persons representing it, we may want to see this question as irrelevant and maybe an issue that may never arise. However, the scenario highlighted at the earlier part of this discourse is on all fours with this question. Firstly, the company has a corporate structure and not every officer, agent or employee may expressly assent to some actions or inactions of the company. Also, the principle of separate legal personality of company is very significant in answering the question. This principle of separate legal personality establishes the general rule that corporate entities are legally distinct from their officers, agents and employees. The implication of this principle is that as a general rule, a company shall be particularly held liable for actions and inactions and not the officers, agents or employees. This is popularly known as the veil of incorporation.

There are circumstances where the veil of incorporation will be pierced or lifted and the liability of the company would extend to the directors and shareholders of the company as officers. In this regards, the shareholders and directors of the company would be treated as one with the company and held liable for the debt of the company. The principle of piercing or lifting the veil of incorporation enunciated from the English case of Salomon v Salomon & Co LTD where it was posited that “if the company was for an unlawful purpose, or to achieve an object not permitted by the provisions of the Companies Act, the appropriate remedy (if any) would seem to set aside the certificate of incorporation, or to treat the company as a nullity, or, if the appellant has committed fraud or misdemeanor… he may be proceeded against civilly or criminally”. However, it should be pointed out here that there are conditions that have to be met before the veil of incorporation would be pierced by courts. One of the conditions that particularly relates to this discourse is a situation where the company is used as a cloak for fraud.

Contrasting the various principles highlighted in these discourse and the scenario we started with, it may not be erroneous for us to argue that the action of the court in remanding an accused person who just facilitated the transaction between the complainant and the company for fraud was a bit out of line. Not just the court here, it is also evident that the police did not conduct reasonable and thorough investigations before charging the matter to court. Reason being that; whether or not the accused person had unconsciously elevated himself from just a client of the company to an agent, the transaction itself was between the company and the complainant. In fact, the money was paid to the company’s account and not to the accused person in the matter. Clearly, the accused person may just be a victim of circumstances and the fall guy for the failed transaction between the complainant and the company. If proper investigations were conducted, the directors and shareholders as officers of the company would be revealed and since this is a matter of fraud the court could have rightly pierced the veil of corporation for the right parties to be brought before it in the interest of substantive justice.

From a different perspective, if the accused person in the scenario personally acted and defrauded the complainant after presenting himself as an agent of the company without the implied or express authorization of the company, the company would not be held liable for the fraudulent act. In this regards, the company could even institute legal actions against the accused person.

To conclude this discourse, the general rule by virtue of the principle of separate legal personality is that an officer, agent, or employee of a company cannot be liable for actions or inactions of a company as the company is a separate legal entity. However, in some circumstances the veil of incorporation may be pierced and the directors and shareholders as officers of a company can be held liable for the company’s actions and inactions.